海绵城市建设已是全球进行时

近年来,《世界卫生组织公报》《科学美国人》《MIT科技评论》以及美国科学院和美国艺术与科学院学刊物、BBC、美联社、CNN、纽约时报等众多国际知名媒体纷纷报道了中国的海绵城市建设,点击文末链接了解更多报道。

导 读

2023年5月30日,美国非营利性时事评论杂志《Reasons to be Cheerful》发表文章《海绵城市建设已是全球进行时》。

文中写道,不同于由混凝土等不透水材料建造的灰色基础设施,海绵城市等绿色基础设施使城市韧性得以显著提升,城市环境可以更加从容地应对暴雨、洪水、海平面上升等气候危机。本文以北京大学俞孔坚教授及其团队的海绵城市探索为例,介绍了海绵城市理念的应用价值与可借鉴的实践经验。此外,在全球范围内,包括英国卡迪夫市、荷兰鹿特丹市在内的越来越多的城市正在采用海绵城市的建设模式,实现城市的可持续发展。对于许多面临着雨洪风险的城市而言,推进让自然做功、实现旱涝调蓄的海绵城市建设已成为了“必经之路”。

以下为全文原文,查看原文报道请点击https://reasonstobecheerful.world/sponge-cities-china-climate-change-resilience/

海绵城市建设已是全球进行时

Cities Are Becoming More Like Sponges

彼得·杨(Peter Yeung)

From an airplane window, Hainan, an oval-shaped island floating alone in the expanse of the South China Sea, resembles a sea sponge.

In reality, the Chinese province genuinely is a kind of engineered urban sponge, thanks to its pioneering network of green, nature-based infrastructure capable of absorbing storm floods and soaking up heavy monsoon rains.

“If you want to survive, you have to be spongy,” says Yu Kongjian, dean of Peking University’s College of Architecture and Landscape Architecture, and founder of Turenscape, one of China’s largest landscape architecture firms. “Trying to protect cities with hard, gray infrastructure made of concrete is doomed to fail.”

Over the years, many architects, engineers and city planners have espoused the value of, and need for, effective water management in urban areas. But Kongjian was the first to propose the holistic concept of the “sponge city.”

三亚红树林生态公园——海绵城市项目 © 土人设计

三亚红树林生态公园内指状相扣的水道 © 土人设计

The idea is not to install enormous artificial foam structures across urban areas, but rather to create cities filled with natural spaces such as parks, lakes and wetlands—which are capable of absorbing, storing and cleaning rain and floods—as well as smaller tools like bioswales, rain gardens, permeable pavements and green roofs. Such “green and blue infrastructure” is in contrast with the manmade “gray infrastructure” that fills most cities—think concrete walls and hard flood barriers, which cause water to build up on surfaces and limit collection of valuable groundwater for drinking, irrigation and more.

While good water management has always been essential for cities, climate change, which is bringing more extreme rains and floods and causing sea level rise—combined with urban growth into more vulnerable areas—has made it an even bigger priority.

“One of the problems all cities are facing is that as they are growing, they are simply cementing over all the land,” says Asit K. Biswas, an expert in water management and distinguished visiting professor at the University of Glasgow. “So the water that used to percolate to the ground doesn’t anymore. Flooding becomes an issue, and important groundwater isn’t replenished. That is why we need sponge cities.”

This emerging approach to urban water management also soaks up all kinds of other benefits: green, nature-based spaces provide habitat for wildlife and areas for exercise and relaxation (which can boost the physical and mental health of residents), as well as likely increasing the value of surrounding property and the city more widely.

三亚东岸湿地公园——海绵城市项目 © 土人设计

Kongjian’s “sponge city” idea is inspired by the ancient Chinese agricultural approach to water management. For centuries, rural farmers have carved out rice terraces across China’s southwest region and beyond, using basic “cut and fill” methods to cultivate mountainous terrain with water-filled paddies. In Kongjian’s hometown, there were seven water ponds, which helped manage monsoons. Many other civilizations around the world, he adds, also have monsoon- and flood-adapted ways of life.

“This is not just primitive agriculture by valley-dwelling peasants,” he says. “It is a cultural heritage that is built on 5,000 years of water management experience.”

Kongjian’s theory dates back as far as 2003, when he observed that “natural wetlands along rivers can function like sponges to retain water during flooding and recharge water during drought.” But it was a decade later, in the aftermath of floods in the capital Beijing that killed 79 people, that China launched the Sponge City Program with pilots across 16 cities (14 more have been added since). By 2030, China’s sponge cities aim to process 70 percent of rainwater across 80 percent of their land.

Hainan, which frequently suffers from severe floods due to its monsoon climate coupled with the worsening effects of global warming, was picked as one of the project’s leading demonstration sites.

In 2015, the local government and the national Ministry of Housing and Urban and Rural Construction kickstarted efforts to transform the island’s two major cities, Haikou and Sanya. Kongjian and his team began by giving presentations on the “Sponge City” concept and ecological restoration—these were mandatory for officials—and developing a mass public information campaign to gain community support. Crucially, a “water-based ecological infrastructure plan” identified at-risk areas and how to protect them with wetlands, rice paddies, parks and coastal habitats.

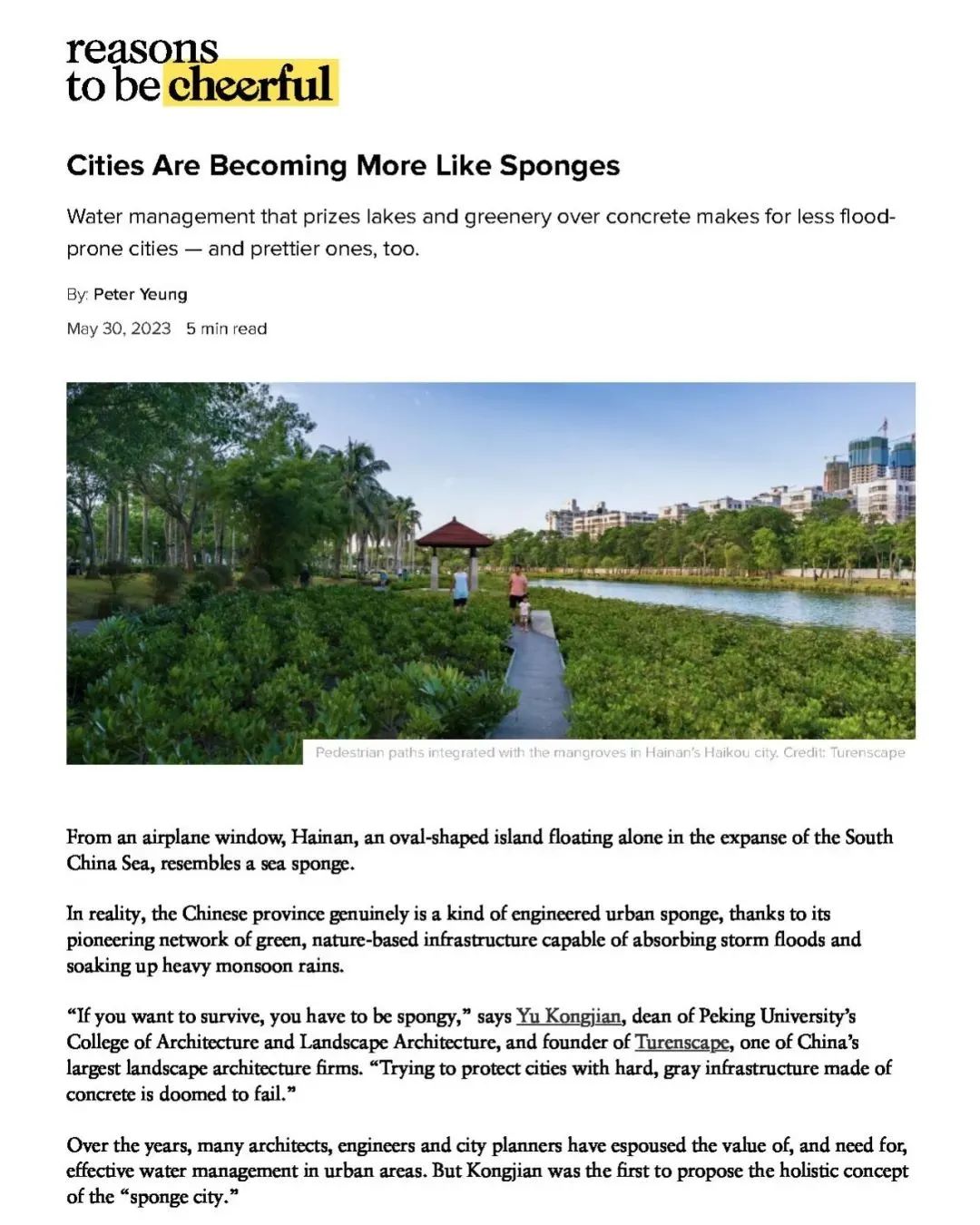

In Haikou, which is home to the 23-kilometer-long Meishe River, the concrete flood walls were removed, and the surrounding area was turned into a mangrove restoration project with floodable pedestrian paths running through it. In addition, terraced wetlands were added to help process 6,000 tons of treated wastewater per day, improving the water quality from grade V (the poorest surface water quality) to grade III (non-potable water clean enough to swim in). Similarly, in Sanya, an “interlocking finger design” of waterways was constructed to buffer the force of ocean tides hitting the coast. Green terraces were added, staggered from the 9-meter-high street level down to sea level, with channels known as bioswales used to capture stormwater runoff.

海口美舍河凤翔公园——海绵城市项目 © 土人设计

“Inundation has virtually stopped,” says Kongjian.

Other efforts to turn Chinese cities into sponges have also proven effective. A study of Wuhan found its 389 sponge city projects across 38.5 square kilometers have not only reduced flooding, but sequestered 725 tons of CO2 a year, reduced temperatures by more than 3°C (5°F) and more than doubled the value of the land.

Adoption of the sponge city model is increasing globally, too. More than 100 “rain gardens” have been built in the Welsh city of Cardiff, which soak up 40,000 square meters of rainwater each year, lessening the burden on the sewer network. Philadelphia’s $4.5 billion Green City, Clean Waters plan, which will run until 2036, is already keeping 2.7 billion gallons of stormwater runoff and sewer overflow out of local waterways. The Orbital Forest of Tirana in Albania will see the city surrounded by a ring of two million trees, which will clean the air, limit urban sprawl and provide flood protection. In the Dutch city of Rotterdam, blue-green roofs have reduced water treatment costs by $75,000 annually and prevented roughly 10,000 tons of CO2 emissions.

Meanwhile, although the Global South is disproportionately suffering the effects of extreme weather, studies show there is an opportunity for cities worldwide to grow sustainably through nature-based infrastructure. A study by design firm Arup found that it is 50 percent more affordable than man-made alternatives, and 28 percent more effective.

Yet there are limits to what a sponge city can withstand. Research published in The Royal Society scientific journal found that while sponge cities should be able to process 1-in-30-year rainfall events, 19 of the 30 pilot cities in China have experienced flooding since 2014. Some 14 million people were impacted by floods in the city of Zhengzhou in 2021. Nearly 400 people died or went missing.

“Sponge cities can maybe deal with sea level rise of one or two meters, but five meters? No,” admits Kongjian. “But if the sponge city can’t stop it, nothing can. You have to move the city away.”

美舍河边的人行步道与红树林融为一体 © 土人设计

Part of the problem, according to Faith Chan, head of the School of Geographical Sciences at University of Nottingham Ningbo China, is that the current sponge city efforts are not genuinely citywide.

“Currently it’s too focused on small-scale green space development to solve the water problem in the ideas of construction,” he says. “The projects shouldn’t just focus on a district or set of apartments. It has to be connected with larger areas.”

Lack of land availability, the need for political support and significant financial cost are also barriers, according to Biswas, who has carried out work in China since the 1980s. “It’s true that retrofitting or reconstructing cities is expensive,” he says. “And while new sponge cities are cheaper, most of the world lives in old cities.”

But Kongjian, whose firm has carried out over 1,000 projects across 200 cities, says that the sponge city model is improving day by day as the evidence base grows. He calls the recent spongification of Bangkok’s Benjakitti Forest Park a “great success” that has already stood up to city flooding.

“This is not something luxury; you have to do it,” he says. “Resiliency is key.”

泰国曼谷班加科特森林公园俯瞰 © pierrick

班加科特森林公园内湿地周边相互交织的栈道 © 土人设计与泰国阿颂·信建筑事务所

部分海绵城市相关国际报道:

世界卫生组织:海绵城市让人类更健康

BBC:应对气候变化,他将城市变成海绵

CNN:城市设计应以水为友、与水共生

文章来源:https://www.cnn.com/2023/03/26/world/flooding-cities-water-design-climate-intl/index.html

《麻省理工科技评论》:中国设计师提出人类需要“与洪水为友”

文章来源:https://www.technologyreview.com/2021/12/21/1041318/flooding-landscape-architecture-yu-kongjian/

《纽约时报》:把城市变成拯救生命和财产的海绵

文章来源:https://www.nytimes.com/2022/03/28/climate/sponge-cities-philadelphia-wuhan-malmo.html

编辑 | 周舟,田乐

制作 | 周舟

版权声明:本文版权归原作者所有,请勿以景观中国编辑版本转载。如有侵犯您的权益请及时联系,我们将第一时间删除。

投稿邮箱:info@landscape.cn

项目咨询:18510568018(微信同号)